Reflections on The Astral Exploration Editorial Department (Spoilers Ahead)

There’s nothing more fitting than ending a day spent agonizing over the meaning of life with The Astral Exploration Editorial Department. It feels as though life’s serendipity was meticulously arranged. But of course, it has nothing to do with me. The world moves forward according to its own logic, and I’m simply delighted by this fleeting moment of resonance and emotion.

I kept wondering whether Tang Zhijun was already mentally unwell. He cautiously uttered absurdities, believed in people no one else would trust, yet maintained his composure in moments of despair. He wrote poetry with fragmented words in the face of a dull, unfeeling reality. As an editor who has spent a lifetime searching for aliens, he could never let go of any clue, and his fantasies must have long since seeped into reality. As a father whose daughter was taken by depression, her pain and confusion transferred entirely onto him. He couldn’t give up answering her question: “What is humanity’s significance in the universe?”

What is the meaning of human existence? Sam Harris once said that the anxiety surrounding this question is “a psychological problem disguised as a philosophical one.” Did his daughter take her life because she couldn’t grasp the ultimate meaning, or was she overwhelmed by unbearable pain? It’s hard to say. Yet, “the owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.” It is pain and anguish that necessitate thought. Without problems, there’s no need to find solutions. Psychological struggles cannot be avoided, but humans do need to find a reasonable explanation for the suffering they endure—or perhaps, out of sheer curiosity, to solve the alluring mysteries of existence.

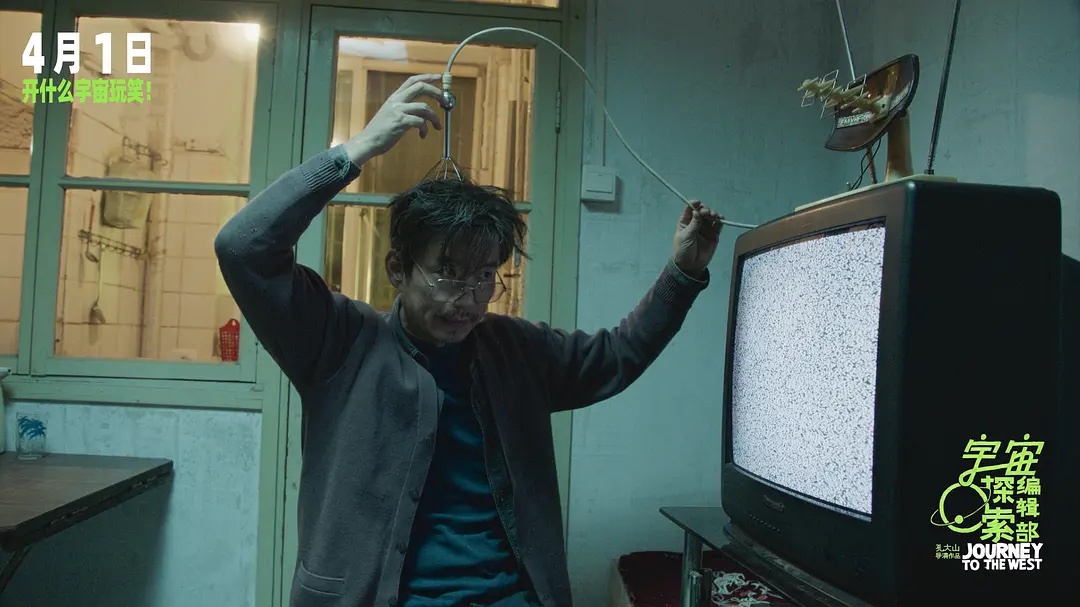

To idealists who love to ponder: I hate to see you struggling. The opening scenes of Tang Zhijun—weak, lonely, and destitute—felt like a bone-chilling wind puncturing the bubble of ideals I had carefully inflated. Dreamers may sometimes need to give up their last material possessions for the sake of heating. The vessel of their ideals—a cherished astronaut suit—is mere scrap in the eyes of others.

To those who love poetry and distant horizons: I hate to see you confined to the mountains. With a pot on his head, Sun Yitong explored the possibilities of language at the edges of reason. Day after day, in a village where everyone could hear his broadcasts, he recited the poems he had just written. To others, his words were noise, and I don’t even know what he truly wanted to say.

The rational Xiaoxiao, the hysterical Qin Cairong, and the perpetually unawake Narisu all, to varying degrees, lived in dreams of finding extraterrestrials, pursuing activities considered utterly meaningless by real-world standards.

But who is more absurd: Tang Zhijun and his crew or the detached onlookers? Camus says the world is absurd and meaningless. If that’s true, then in this absurd world, some stumble through life as society trains them, doing jobs they hate, driven by jealousy and greed. Others, abandoning material desires, fill their hearts with the act of searching. Who is more absurd? Equally absurd, but neither is shameful.

In the end, birds perched on the stone lion, the scammer’s bone lengthened as promised, the donkey found its direction, the aliens’ spacecraft was discovered, and Sun Yitong flew away. Having “witnessed” it all, Tang Zhijun concluded his journey.

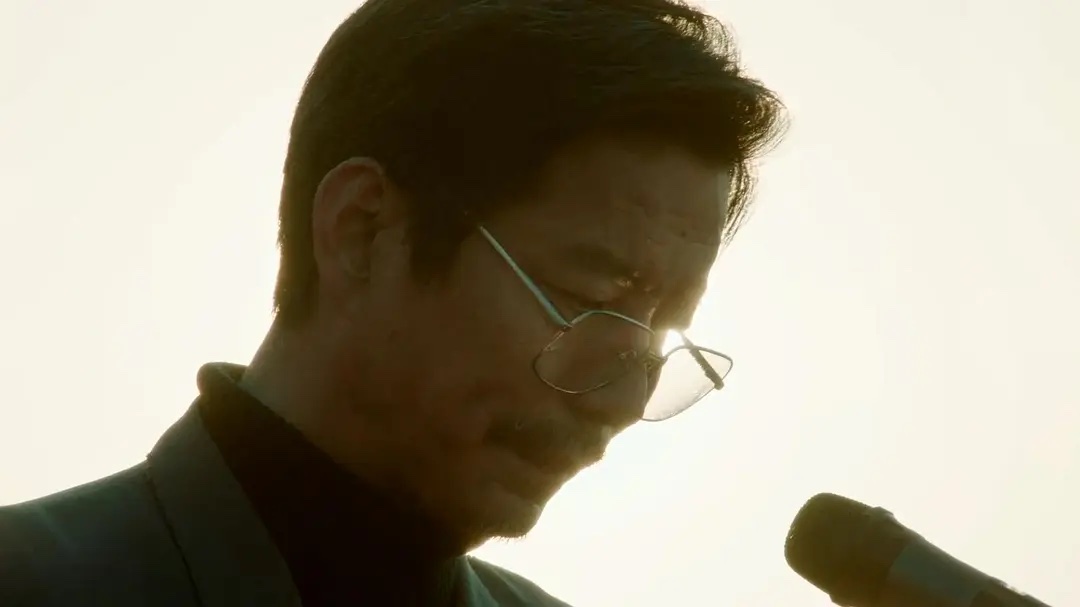

The shaking camera, the oppressive mysteries—it made me nauseous at times. But eventually, Tang Zhijun’s ill-timed monologue arrived. Who gives a speech about life’s meaning at someone else’s wedding? And who, at dusk, steps onto a platform to answer his daughter’s question with restraint, tears, and silences? This was the best ending.

For me, meaning cannot exist without a subject. The subject is the one who defines and owns meaning. Humanity’s significance, to the world (objectively), cannot be discussed because there is no subject. To humanity as a whole, the answer might be boring: to simply continue existing. Every individual inherits a sense of meaning from society and family to varying degrees, yet no one needs to be bound by it. One can choose independence, to seek resonance with nature or with others. Meaning shifts constantly; only the sense of meaning in the present moment is real. If someone feels that something meaningful must benefit the future, it’s merely how they feel in the moment. When the sun rises tomorrow, they might have a new sense of meaning, craft a new story to explain themselves, and live a different life—just like Tang Zhijun’s rebirth. Like everyone who carefully guards their sense of meaning, they deserve respect.